Once upon a time, when dirt was young, and rocks were soft, a young boy wanted a lathe. Not having great sums of money to buy one, or much of a clue about how to go about it anyway, he bided his time, reading reprints of 19th century machinist’s books on lathes. He pondered using his University’s foundry to make parts to *make* a lathe, but didn’t quite get rolling on that. (Thankfully) Eventually, he looked at the lathes in his Metalsmithing department, to ponder their construction. One was a giant old LeBlond Regal, built in 1942, weighing in at about 4000 pounds. Way too complicated to make. One was a Prybill spinning lathe. Big, heavy, and old, but not much of a metal cutter. It was intended for forming metal instead of cutting it. Neat, but not what I wanted back then. (Now I want one, but it’s years later.) Hidden in the gloom under the Prybill’s bed was something that looked sort of like part of a lathe. Digging further, more parts came to light. It turns out there was an entire small lathe buried under there, in pieces.

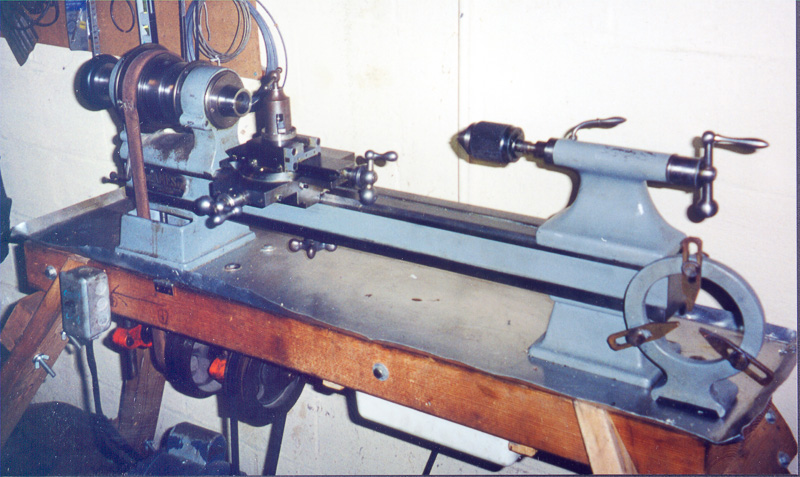

It was an Ames AM-1, also built in 1942, but a much smaller machine. About 200 pounds when it’s all together, it looks very much like an overgrown Boley style watchmaker’s lathe. Instead of a bed 12″ long, the Ames is 3 feet long, and can take a 1″ bar through the headstock. A headstock which runs in precision ball bearings, and uses collets. Weird ones, but collets. Fortunately, there was an entire set of the freak collets to fit it, as well as 3 and 4 jaw chucks, and all of the pieces parts to make it work, except the wooden bench it had once lived on. Not a problem. I promptly built a bench for it that looked like a vastly overbuilt wooden sawhorse, if sawhorses had solid 8″x6″ beams as their tops. It was a bench that was designed to support the lathe, and be easy to move. Which it did splendidly, even if it did look a bit…crude. A look that wasn’t helped when I found some scrap aluminum sheet several years later, and quickly bashed the edges up to make into a chip pan. Probably should have taken more time to make the pan edges neat, but that really wasn’t the priority that summer. Making money with the thing was.

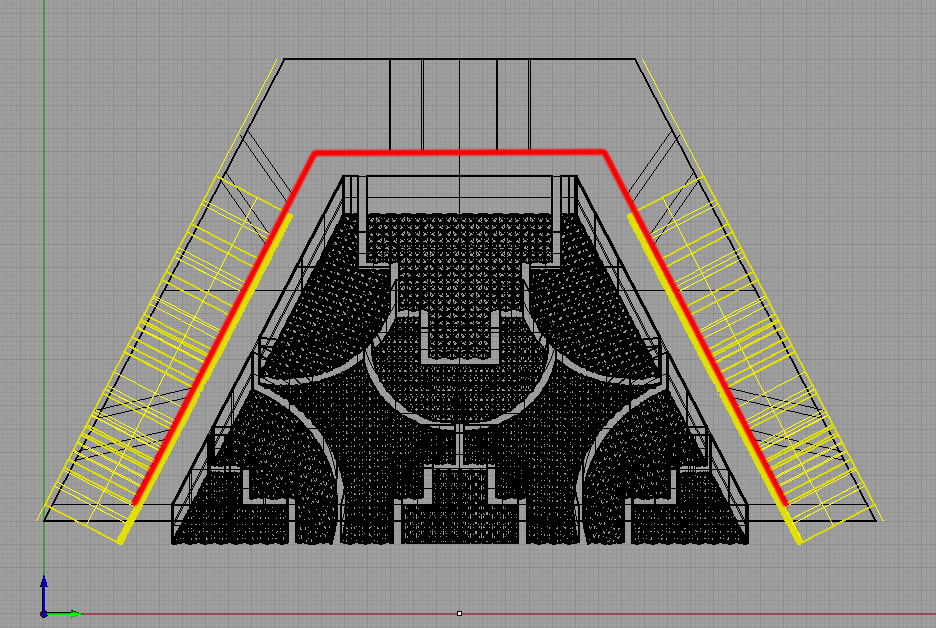

The Ames, as set up in the basement, complete with sawhorse stand.

The Ames, as set up in the basement, complete with sawhorse stand.

Returning to the excavation of lathe bits from under the University’s spinning lathe, I talked with my professor to see what the story was with this pile of lathe parts. Turns out it was a lathe that he’d inherited when he took over the department. Didn’t have much use for the lathe, but he did like the workbench it had been on. So he’d pulled the lathe off, stored it, and repurposed the bench as a drillpress stand and worktable in the back room, right near the rest of the lathes. I’d been storing parts on the bench without realizing what it was. The bench being furniture, and the lathe being what I wanted, I concluded a deal with him where I traded polishing every stake, hammer and anvil in the shop for this little lathe. Which sounds like a deal, until you realize that the professor in question was Michael Jerry, and he’d taken over the shop from John Marshall. Both noted silversmiths. There were 5 anvils, 120(ish) large stakes, and about 300 hammers. Took me nights and weekends for most of a semester to get that thing paid off. On the other hand, it did teach me how to polish hammers in one hell of a hurry, a skill which has stood me in good stead all the years since, so I still call it a pretty good deal.

I spent the rest of that semester rebuilding the thing, putting new bearings into the headstock, and generally putting it back into something pretty close to new condition.

Took it home that summer, set it up in the basement, and proceeded to use it to make brass handled stiletti for the reenactor market. One of the really nice things about the Ames is that it has an indexing system built right into the headstock. So you can use it to make equally spaced holes (or grooves) around the circumference of a piece held in the lathe. Make yourself a tool to hold a flex-shaft handpiece onto the toolpost, and suddenly you can use it to set stones into the sides of your little brass dagger handles, or to do evenly spaced eternity rings, or all sort of other decorative things. Bigger lathes don’t have this capacity, but the Ames does, and it’s quite handy.

So this machine became my baby, and I used it quite a lot in the next few years, even as I gradually gained access to larger and ‘nicer’ machines. The Ames was originally intended to be a high-precision instrument maker’s lathe, so it doesn’t do hogging or roughing all that easily. What it does is go very fast, while remaining rock solid, to enable me to cut very small things to very tight tolerances. So I eventually picked up an even older (if larger) ‘normal’ lathe to use for larger, or rougher work, so as to baby the Ames, and reserve it for the jewelry class work it was designed for. The 1″ Ames machines are pretty close to my idea of the perfect ‘jewelry’ lathe. Big enough to be solid, yet small enough to be portable, with enough headstock capacity to handle making just about any kind of tooling the average jeweler needs.

After about 10 years of using the thing pretty regularly, life happened, and I moved to the west coast, leaving the Ames mothballed in Ohio, for what was supposed to be about 18 months. Not exactly. Now it’s about 18 years later, and that Ames is still covered in rust inhibitor, down in the basement. And I have three more in the garage, here in California.

It all started with wanting a spare toolpost.

The most fragile part of the Ames is the XY toolpost. They do eventually wear, and spare parts haven’t been made in 70 years. So I decided to look for a spare on Ebay. Found one pretty quickly. For about $300. Yikes! But wait a sec, for another $200, I can get the entire rest of the lathe to go with it, including another set of the rare collets, which tend to go for about $300 all by themselves. Well, that’s a pretty easy decision. $500 later, plus the cost of truck freight from North Carolina, I have Ames #2, in pieces, in the garage. And now I have…not exactly a spare toolpost, but at least enough parts to keep one lathe going no matter what…, as well as an Ames in California with me.

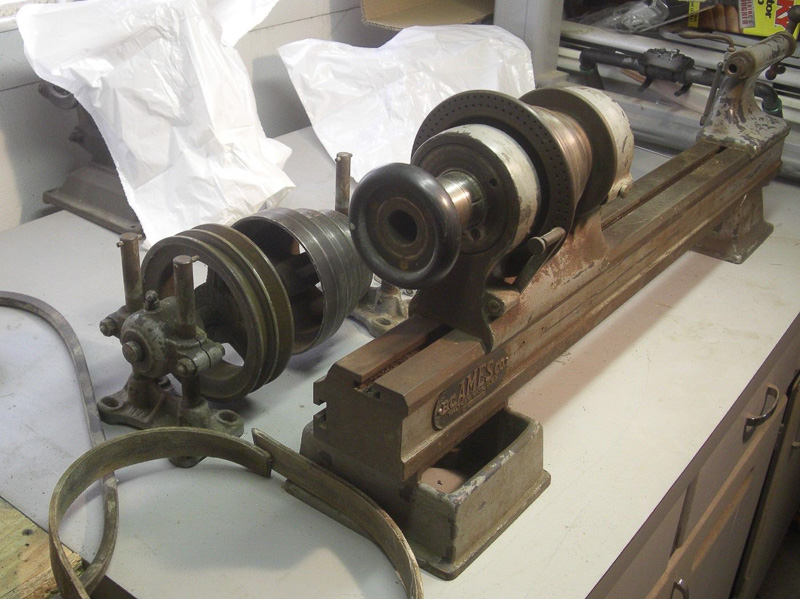

Most of Ames #2, before it shipped to me. If you look at the big ring in the middle of the headstock, you can see the little holes of the indexing system

Most of Ames #2, before it shipped to me. If you look at the big ring in the middle of the headstock, you can see the little holes of the indexing system

But I still need a spare toolpost.

Several months later, it was back to Ebay, still looking for a spare XY unit. Didn’t find a toolpost, but I did find the rotary milling attachment. Which lets you grab a part in a collet, then put a cutter in the nose of the Ames headstock, and use it sort of like a milling machine with a rotary index. Wonderful little device. Only problem is that it takes an entirely different set of antique, obsolete, rare, freak collets, and it only had one with it. But I know some people who have spare sets, so the milling attachment came home with me, collets or no.

Eventually, another Ames floated by. This time, it was one of the exceedingly rare 3 bearing chucker lathes. These were designed for high precision production work, and had a different headstock (which happens to use the same secondary set of freak collets as the milling attachment). These were never common machines, and I’ve never seen another one. This lathe had not one, but two XY units with it, as well as what looked to be two full sets of the even freakier little collets, as well as the lever action tailstock for production work. All for about the cost of one of the collet sets, plus yet another call to my friendly truck freight guy. (Who is now on speed dial.)

Lathe turned up a few weeks later, and I have to say it’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen. Made in about 1920, if the serial numbers are right, and it clearly had a long and productive life. Most of it is if not junk, not far from it. The fancy headstock is probably salvageable, but that’s about it. Turns out one of the XY units came from an entirely different machine, and one of the sets of collets fits yet a third small lathe (not an Ames), but it did have a full suite of collets in pretty good shape, as well as a number of spares. The main Ames XY unit was scrap. On the other hand, cleaning up and selling off the non-Ames parts will probably net enough cash to get me out of it in good shape, so other than some time and effort, there’s no great loss, and I did get some spare parts.

Ames 3 Bearing Chucker lathe.

Ames 3 Bearing Chucker lathe.

But I still need a spare XY unit.

Back to lurking on Ebay. Several months later, another Ames turns up complete with all sorts of tooling and extra widgetry that I’d also been looking for. But I need a fourth Ames like I need a hole in the head. So I contacted the seller to see if he’d break up the lot, and just sell me the accessories I was after. That didn’t work out, but it turns out he did have yet another Ames, complete with the oak workbench they’d come with originally. As well as several spare headstocks, tailstocks, and collet sets of various types. He’d sell me the bench by itself, or the whole mess for a mere $200 more. Only one XY unit though, so I’d still need a spare. However, it did have the overhead drive unit, complete with working transmission, a very, very rare find. I really wanted the bench, to get my favorite, original Ames up and off the sawhorse she’s been sitting on for 25 years. It had a few issues, like a missing drawer, and a really fugly sheet metal top and some genius had slathered it down in red paint, but other than that, it looked OK in the pictures….

I figured I’d just replace the top, strip the paint, and away I’d go. I’d restored an oak watchmaker’s bench of similar vintage a few years back, and it had turned out beautifully. So nicely in fact, that we use it as the backdrop bench in all of the Knew Concepts adverts that show a bench. I had high hopes that this would turn out equally well.

One more call to my truck guy, and the thing was on the way.

Ames #4, with oak workbench. The two vertical black things are the cast iron uprights that support the overhead drive transmission. This is probably one of the last machines that still has that system in working order.

Ames #4, with oak workbench. The two vertical black things are the cast iron uprights that support the overhead drive transmission. This is probably one of the last machines that still has that system in working order.

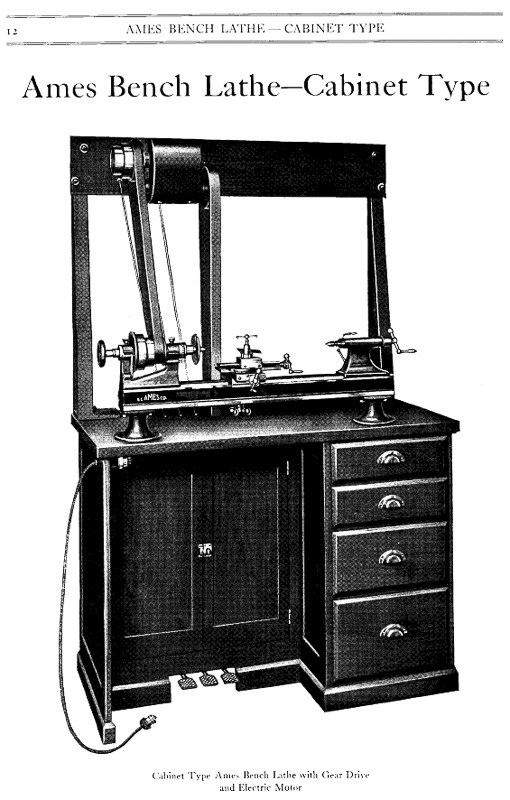

What it looked like originally.

What it looked like originally.

The motor is behind the doors at the bottom. The first belt runs 6 feet vertically up to the transmission box mounted on the cross shaft at the top of the cast iron arms. Speed is controlled by the pedals at the bottom. They have cables that run up to pull on levers on the back of the transmission case, 6 feet away. There are two speeds ( High and Low) as well a reverse. All are instantly selectable by pressing the pedals. Power runs down to the lathe through a second leather belt, which can give three different speed selections, for a total range of 6 speeds. (Don’t know what they were yet, haven’t finished fixing the transmission to the point where I can figure out the differentials.)

This particular machine was built in 1928, by the serial numbers. Allowing for 87 years of wear-and-tear, everything’s still there, and most of it still works. Turns out that under all the grey paint, the transmission case is solid bronze. So when it’s all done, it’s going to look very steampunk. Except this thing will actually work.

This is the first in what will be an ongoing documentation of what it took to get the thing back into action. I wasn’t actually looking for one of the overhead drive units. I didn’t think there were likely to be any survivors. But since I’ve got one, it’d be wrong not to use it. Especially since it still works, and seems to be in pretty good shape.

Stay tuned, to learn far more than anyone wanted to about the details of 1920’s furniture construction, and how wood construction can either fail or survive, over the span of nearly a century. A good chunk of the motivation here is just to leave a find-able record of the details. Hopefully, this will be of some use to the next poor bastard who has to do this.

-Brian

Oh…. And I still need a spare toolpost.

{ 0 comments }

Latest posts by Alberic (see all)

- Ames Lathe rebuild, part 1 of (Ghu only knows…) - September 10, 2015

- Digital Saxons - January 8, 2013

- More Watchmaker’s Bench Press - November 21, 2011